In the second half of the 19th century, Europe’s ports were suffocating from their own success. Cargoes arrived in ever-increasing volumes, and old steam mechanisms couldn’t keep up with the pace of the industrial age. It was then that a solution came from Liverpool that changed the course of port history. Sampson Moore, an engineer and entrepreneur, developed the world’s first electric gantry crane, a type of overhead crane. His machine allowed heavy artillery to be loaded faster, more accurately, and more safely, and soon the technology migrated from military arsenals to the docks. But before this revolutionary idea was brought to life, the man who created it had to emerge. The continuation of this innovation story is available at liverpool-future.com.

Who Was Sampson Moore and Why Is He Worth Knowing About?

Sampson Moore was born in Liverpool, a city that was rapidly growing at the time due to maritime trade and heavy industry. It was here, among the shipyards and factories, that his engineering imagination was formed. He founded the company Sampson Moore & Co., which specialised in the production of large metal structures and military mechanisms. The company was located in the very heart of Liverpool, a city with direct access to global markets and, most importantly, to the sea.

Moore worked at the intersection of the military, industry, and new technologies. As early as the 1850s, his company was producing engineering solutions for the British fleet, including naval mortars. But the real breakthrough came in 1876, when Sampson Moore & Co. designed and manufactured the world’s first electric crane for the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich. Moore experimented with a new energy source and laid the foundation for an entire field of engineering. His solution did not remain a niche one. The technology was soon adapted for industrial enterprises and ports that demanded ever-greater efficiency.

It was from Liverpool that the man who first proved that electricity was a step forward in logistics, construction, and military affairs. And although Moore’s name is not widely known today, his invention is used daily in dozens of ports around the world—albeit in modern, automated versions.

The Electric Crane – a Breakthrough No One Expected

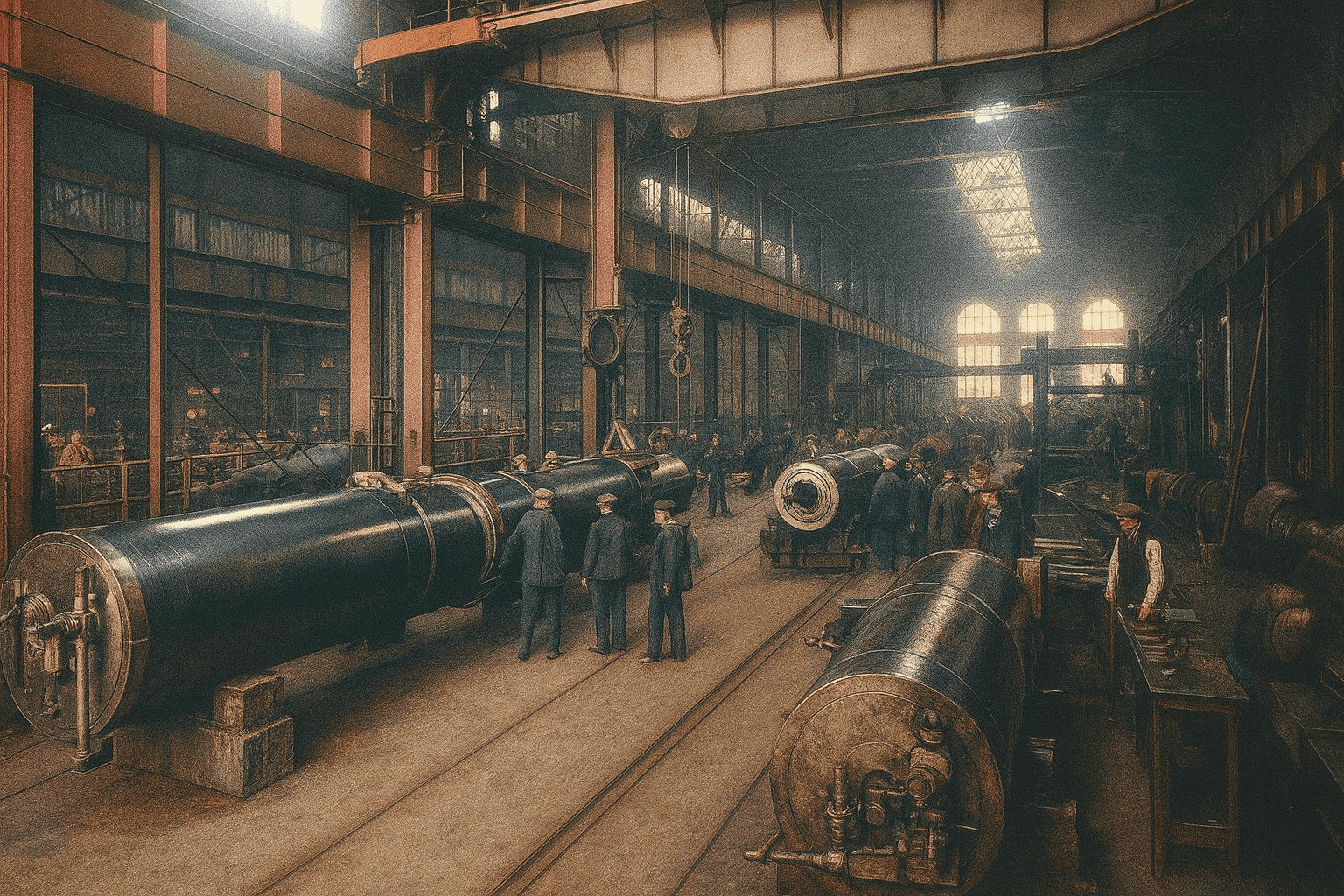

In 1876, Sampson Moore designed and manufactured a crane for the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, a key military complex near London. This device became the world’s first electric gantry crane: a large structure on supports, with a lifting mechanism moving between them, capable of moving heavy artillery with a precision and speed that steam engines could not provide. For the first time, an electric motor became the heart of not a laboratory experiment, but a fully practical engineering solution.

Before this, lifting mechanisms were powered by either steam or hydraulics. They were massive, difficult to maintain, and dependent on centralised energy sources. Moore’s electric crane changed this logic. It operated autonomously, allowed for precise control of movements, had fewer energy losses, and responded faster to commands. Its design also proved to be versatile: the same principles could be applied for both military and civilian purposes.

The key was that the electric motor allowed the crane to be placed exactly where the work was needed—without being tied to steam boilers or hydraulic systems. In the case of Woolwich, this allowed cannons to be moved inside the arsenal with unprecedented precision. The technology was quickly noticed and began to be used by civilian enterprises working with heavy metals. Ports soon followed suit.

This electric crane became the prototype for new infrastructure: mobile, efficient, and independent of old energy systems. At the time, it seemed like a technical novelty, but within a few decades, electric cranes became the standard for port logistics worldwide.

How This Invention Changed Ports Around the World

What began as a military development quickly found a second life in the civilian sector. The port industry, which at the end of the 19th century desperately needed more efficient solutions, embraced Moore’s electric crane as a breath of fresh air. Compared to its steam counterparts, the new type of crane was more mobile, simpler to install, and cheaper to operate. It could serve several ships in one shift—which even then meant a significant economic impact.

The technology was first adopted by companies in the north of England—particularly those working with metal, coal, and heavy machinery. But by the beginning of the 20th century, electric cranes began to appear in seaports. In 1892, the British company Stothert & Pitt installed an electric port crane in Southampton—using the same principle that Moore had pioneered, but adapted for working with containers and cargo in a port setting.

The revolution lay in its versatility: electric cranes could be scaled, customised for different needs, and placed without cumbersome infrastructure. Their use reduced downtime, cut maintenance costs, and accelerated processes. From Liverpool to Rotterdam, from New York to Singapore, the new technology became an integral part of the port landscape. And although Moore himself did not live to see his invention gain global prominence, he changed the way the world moves goods.

It was thanks to this solution that the port ceased to be a place of slow, arduous labour—it became an ingeniously designed system that works quickly, accurately, and without failures. And it all started not in a major metropolis’s harbour, but in an engineering workshop in Liverpool. And our city is known for its innovations, even in art.