Amidst the fogs of the 18th century, when the English coast claimed hundreds of ships each year, one man in Liverpool decided to change the rules of the game. Former privateer William Hutchinson, who had become a dock master, held neither a scientific degree nor patents. Yet it was his idea—to install parabolic reflectors in lighthouses—that helped turn a faint flicker into a clear, directed beam of light. It was a moment when navigation became more precise, and human lives less vulnerable to the darkness. How it happened and what its significance was—on liverpool-future.com.

The Background and Personality of William Hutchinson

It’s hard to imagine that the man who changed the principle of how lighthouses work started his life not in a workshop or a lab, but… on a ship’s deck. William Hutchinson was born in 1715 and was a sailor from a young age—not just a merchant, but a privateer, meaning a captain officially authorised to attack enemy ships. This experience taught him the most important lesson: the sea does not forgive carelessness. It was this understanding, gathered from voyages, storms, and moorings, that would later be embodied in a series of practical, almost intuitive inventions.

In the mid-18th century, Hutchinson became the dock master of Liverpool’s docks—a position that required a keen eye and technical ingenuity. But he didn’t limit himself to administrative routine. William systematically kept records of tides, currents, and atmospheric conditions—doing what we would today call field research. It was his journals that would later form the basis of the first British tide tables.

But Hutchinson’s name shone brightest thanks to another innovation—an attempt to improve the work of lighthouses. Imagine a barely glowing lamp with candles or oil, hidden inside a damp stone lighthouse tower. This was not enough to guide ships in fog or during a storm. The inventor decided: if the light cannot be made stronger, it can be concentrated. This is how the idea of a parabolic reflector arose—a simple but brilliant system that changed the nature of maritime navigation.

The Invention of the Parabolic Reflector: Idea, Implementation, and Technique

1763. At the Leasowe Lighthouse, near Liverpool, the first parabolic reflector in Britain (and possibly Europe) was installed. This device had a simple purpose: to collect the scattered light of candles and direct it into a single, clear, horizontal beam. The light seemed to start “speaking” to sailors, piercing through fog and darkness. The initiator of this technical breakthrough was not a physicist or an inventor by trade, but William Hutchinson—a man who sought practical solutions for real problems.

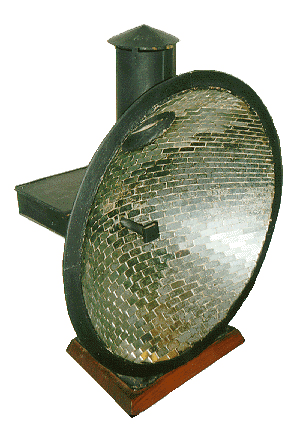

The reflector consisted of dozens of small mirrors or silver-plated metal fragments mounted onto a paraboloid-shaped base. It was made of wood or alabaster, sometimes using a plaster base that replicated the geometry of a parabola. The size of such a mirror could reach 12–13 feet in diameter—a true mirrored “sail,” only it was tuned to light.

The light source—usually a few candles or an oil lamp—was placed at the focus of the paraboloid. As a result, the light rays that would normally scatter in all directions were now directed almost parallel, creating a strong and concentrated beam.

Importantly, the idea of focusing light was not entirely new—the paraboloid as a shape had been known since antiquity. But Hutchinson was the first to apply it systematically in lighthouse practice, using accessible materials and simple but effective engineering. In this lies the entire essence of his method: to bypass complexity without compromising the result.

His invention quickly attracted the interest of other engineers. In Liverpool itself, reflectors also began to be used at the Hoylake Lighthouse. Hutchinson personally monitored their performance, refining their shape, tilt angle, and the placement of the lamps. It can be said that he effectively created the first prototype of an active optical system for maritime navigation—without laboratories, blueprints, or government grants.

Influence on Lighthouse Optics and Maritime Safety

Before the advent of parabolic lighthouses, the light was weak, scattered, and often helpless against the forces of nature. On a clear night, it might be visible from a few miles away, but in fog or bad weather, it became useless. William’s invention changed the very essence of this system. The lighthouse ceased to be just a fire on a tower—it became an optical instrument capable of “showing the way” from a much greater distance.

Light concentrated into a narrow horizontal beam no longer got lost in the sea air. This meant one thing: ships could navigate more accurately, not waste time on careful maneuvering, and were less likely to run aground or crash into rocks. For a port city like Liverpool, with its rapid development and high intensity of sea traffic, this was critically important. And it was also economical. More ships meant more goods and fewer losses.

The technology was quickly discussed among marine engineers and port administration. By the 1770s, similar reflectors were being installed in other British lighthouses. Hutchinson himself held demonstrations—clear, practical ones with comparisons: this is what you see without a reflector, and this is with one. The difference was so obvious that doubts were powerless against the facts.

And although reflectors were later superseded by Fresnel lenses—more efficient and easier to maintain—it was Hutchinson’s systems that became the link that connected a crude fire and precise optics. It was the first major modernisation of lighthouses, making them instruments of safety.

Further Improvements and Significance for Navigation

The idea that William Hutchinson implemented in Liverpool turned out not to be a random experiment, but a solid foundation for the next stage of development in lighthouse optics. As early as the 1780s and 90s, it was picked up by engineers at Trinity House—the institution responsible for navigation equipment in Britain. They improved the design: instead of assembled mirrors, they began to use polished metal surfaces and introduced ventilation to reduce lamp smoke. The light became cleaner and the structures more reliable.

However, the real leap forward occurred in the 19th century when the Frenchman Augustin-Jean Fresnel developed his famous lens. It allowed up to 85% of light to be collected and focused, which significantly exceeded the efficiency of the reflectors of the time. But the idea that light needed to be concentrated and directed had already taken root—thanks to Hutchinson. In this sense, his system was a kind of foundation: the technical thinking did not change, only the tools did.

Moreover, the principles laid down in those first designs became universal for navigation systems as a whole. Modern floodlights, signal towers, even headlight traffic lights—all of them work on the same basis: a maximum of light in the right direction. And although Hutchinson himself had no scientific titles, his practical intuition proved to be no less farsighted than the work of engineers in academic robes.

One could say that he taught light to speak to the sea. And this light still guides ships, even if William Hutchinson’s name has almost disappeared from the radars of history. And while Liverpool’s technical legacy often remains in the shadows, its influence is still felt—in lighthouses, ports, and engineering solutions. Incidentally, just like the open-air theatre in Liverpool, innovative ideas are sometimes born precisely when functionality and inspiration are combined.