The architecture of religious buildings is an interesting topic to explore. Some of Liverpool’s churches have a rather classical appearance, while others have a more original design concept. In this article on liverpool-future.com, we won’t be analysing the beliefs or doctrines of local religious denominations, communities, or organisations. Instead, we’ll focus on the architectural features of their churches and houses of worship.

Liverpool Cathedral

Anglican and Protestant churches are the most numerous in Liverpool. One of the most famous and beautiful in terms of design is the Anglican Cathedral. We have described it in detail before, but here we will mention the main points: this building was created in the Gothic style and has a huge 101-metre central tower. The cathedral took a very long time to build—work began in 1904 and was completed in 1978, after the architect Giles Gilbert Scott, who won the design competition in the early 20th century, had already passed away.

The building is 188 metres long, which, as intended, symbolises the unity of the masses on a giant scale. The initial design focused on the so-called eastern end of the structure, where two towers were planned in the northern part. However, this plan was changed to a symmetrical one, with a single tower. Red sandstone was the dominant material used.

The Gothic design was a condition of the competition—that’s how things were back then. But structural stability was also important to the judges, because if there were any doubts about it, all the beauty would be meaningless. That’s why Scott won, and not, for example, a Mr Mackintosh, who developed an original interpretation of Gothic by combining a traditional plan with modern solutions for better visibility for worshippers.

Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King

This building, also known as the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, is respected for its unique design. Its construction began in 1962 and was completed in 1967. The cathedral, by architect Frederick Gibberd, has a circular shape and a huge conical dome with stained glass that creates an amazing light effect inside.

The structure is a kind of synthesis of architecture, design, and art, with its components designed as separate parts of a great whole. Sixteen huge concrete ribs form the main structure, creating a wonderful example of post-war architecture. Analysts say Gibberd’s cathedral proudly flaunts the bare bones of its modernist essence, although it was once criticised by new Brutalists for a lack of honesty.

St. George’s Church

Some of Liverpool’s churches are connected to the Horsfall family. One of them is St. George’s Church. It owes its existence to Charles Horsfall, who, after many years in Jamaica as a successful merchant, returned to England in 1803 to the Everton district of Liverpool. In 1813, Charles became one of the patrons of the construction of St. George’s Church.

This building was unique for its time—it was designed by James Cragg and Thomas Rickman, who used innovative materials: the internal structure is entirely made of cast iron, and the facade is clad in sandstone. The slate roof rests directly on the metal frame, which makes the building architecturally special.

The destroyed Christ Church

After the death of Charles Horsfall in 1846, his children, led by Robert, founded Christ Church on Great Homer Street in his memory. The project, designed by architect Shellard, helped create a place of worship that was recognised as a true architectural masterpiece. Historian James Picton described it in 1873 as “an unusually elegant reproduction of a 15th-century parish church, executed in white stone.” Unfortunately, the church was completely destroyed during the German bombings in May 1941.

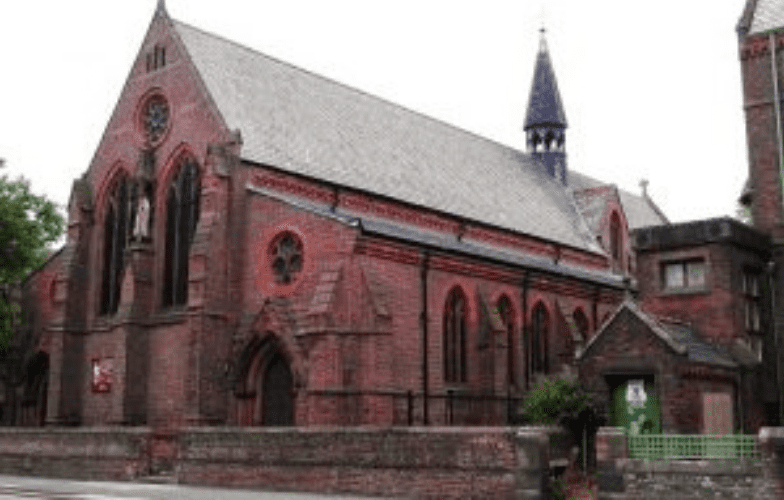

Church of St Margaret of Antioch

Robert Horsfall, a successful stockbroker and supporter of the Tractarian movement in the Church of England, commissioned George Edmund Street, one of the leading architects of the time, in 1869 to build the Church of St Margaret of Antioch on Prince’s Road in Toxteth. At first glance, its facade looks quite restrained—it’s a concise brick building without unnecessary decor. However, its true beauty is revealed inside.

The church’s interior is striking in its richness. Almost every square inch of the walls and vaults is covered in intricate murals and geometric patterns. The ceiling of the chancel is decorated with images of 14th-century angels, each holding a musical instrument. The stained glass is of particular artistic value, among which is a work by Nicholson from 1952. It replaced the windows destroyed during the Second World War. Despite the destruction that Liverpool suffered in the 20th century, St. Margaret’s Church survived both the war and the Toxteth riots of 1981. The memory of Robert Horsfall is preserved thanks to a memorial plaque in the church’s chancel.

Christ Church in Toxteth Park

In the 19th century, the struggle between Tractarians and Evangelicals in the Church of England intensified. The Horsfall family was no exception: Robert supported the former, while his younger brother George was a convinced Evangelical. In 1871, George founded Christ Church in Toxteth Park, not far from St. Margaret’s Church.

The building was designed by local architects Culshaw and Sumners, who created an amazing structure with a tall, unusually curved spire that can be seen from afar. Its interior is distinguished by a wealth of artistic elements, including a stained-glass window by Gustav Hiller depicting the construction of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral. Important details of the church are the reredos and the altar base, designed by the eminent Liverpool church architect Bernard Miller.

St. Agnes’ Church

Built to a design by John Loughborough Pearson, St. Agnes’ Church resembles a scaled-down version of Truro Cathedral. The exterior of the building is clad in red Ruabon brick, but the interior is striking with its Caen stone that adorns the Gothic vaults. Important architectural elements include a sculptural frieze above the apse, created by Nathaniel Hitch, and a stained-glass west window.

St. Faith’s Church

Built for the Anglo-Catholic community of North Liverpool, this church is distinguished by a rood screen made by Venetian craftsmen. Its crucifixion scene provoked strong criticism from Protestants.

St. Paul’s Church

Giles Gilbert Scott’s project, executed in a modernised neo-Gothic style, is the largest brick church in Europe, built with over two million bricks and reinforced with reinforced concrete. The structure became a kind of experimental ground for the architect’s ideas, which he later used in Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral.

Places of worship for religious minorities

Of course, not every religious building in Liverpool impresses with its pomp or architectural grandeur. There are also many smaller religious communities here that have created comfortable buildings for themselves with donations from their parishioners. Sometimes, in such inconspicuous buildings, something no less important than rituals takes place. They are most often created in a simple, minimalist style, adapted for the most convenient biblical study. Among them is the Jehovah’s Witnesses Kingdom Hall on Peel Street, which you can see in the photo.

Thus, the aesthetics of Liverpool’s places of worship demonstrate the evolution of architecture from Gothic to modernism.