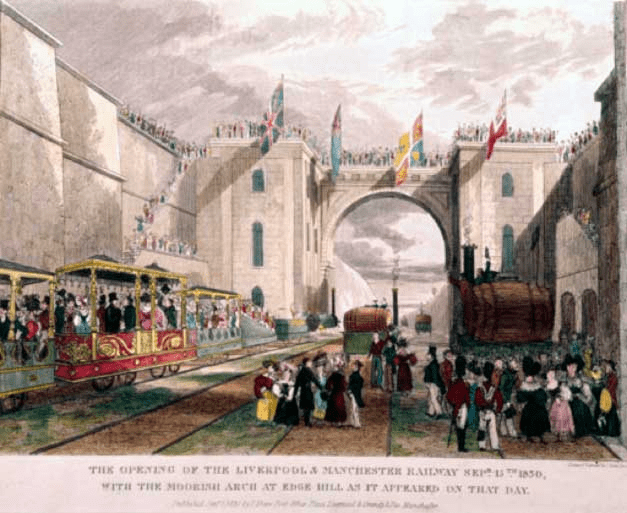

Henry Booth was a British corn merchant, businessman, and engineer. His main achievement for the city and the country was the construction and management of the innovative Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&M), the world’s first steam railway to run regular passenger and freight services simultaneously. Let’s discuss the fascinating history of this innovation and one of its developers on liverpool-future.com.

Biographical information

Henry Booth was born in Liverpool on 4 April 1788. He came from the old Booth family of Twemlow. His father, Thomas, was the son of a middle-class farmer from Orford. Thomas and his brother George started working as apprentices for a grain merchant named Dobson in 1767, and around 1774, they opened their own grain trading firm in Liverpool.

The family, of course, hoped that Henry, as the eldest son, would continue his father’s business. So, he was sent to study in a nearby village with Dr. Shepherd, a Presbyterian clergyman. The boy immediately showed a talent for reading, poetry, and practical mechanics, and also had an excellent sense of proportion. Initially, Henry did work in his father’s business. But he later began expanding his own corn trading business, which, however, was not successful.

The Liverpool-born inventor died on 28 March 1869, enriching the city’s history with his innovations in the railway industry, which had only just begun to develop in the 19th century. So, what exactly did this Liverpool innovator contribute?

Railway construction in the 1820s and 1830s

Booth’s father, Thomas, was a member of the preliminary committee for the L&M railway project in 1822 (some interesting facts about it are mentioned here). Henry later replaced his father and quickly became known for his organisational and promotional skills, as well as his enthusiasm for the project, which had stalled somewhat by 1823.

Booth was appointed secretary of the committee and was second only to Joseph Sanders in his dedication to the project. He was one of four members of the working group who were sent to visit other railways at the Bedlington Ironworks, Killingworth, and Hetton Colliery. Henry returned with a report that recommended a steam locomotive for the L&M. The meeting on 20 May 1824 accepted the report and took steps to create a joint-stock company.

All attention on the L&M

In 1825, Booth sold his share in the corn business to focus on the L&M project. That same year, the project was defeated in parliament because George Stephenson performed poorly. He was a self-taught man rather than a well-trained engineer, and some of his subordinate engineers made the situation worse by making significant mistakes while, as we would say today, giving their presentation. Although Booth asked that no one be made a scapegoat, one of the engineers committed suicide as a result.

The L&M engaged the Rennie brothers to submit a new proposal for railway construction in 1826. The organisation focused on using stationary engines, with mobile locomotives only to be used if their technology improved. Thanks to this emphasis on stationary engines and the involvement of the Rennies, the authorisation bill passed all the necessary stages in the spring of 1826. After this, Booth, Sanders, and other locomotive supporters, to their disappointment, replaced the Rennie brothers, bringing George Stephenson back to build the railway.

On 29 May 1826, after the L&M project was authorised, Booth was appointed treasurer with a salary of £500 a year. He was to continue conscientiously performing the duties of treasurer, secretary, and later, general manager.

A crucial moment: stationary engines or mobile locomotives?

As the railway’s construction neared completion, a dispute arose in the management committee over whether it was better to use stationary engines or mobile locomotives. This was particularly relevant because of the inclines around Rainhill. Booth advocated for locomotive power, but the problem was that the locomotives of the time were mostly designed for hauling goods to and from mines, not for faster passenger transport. The single-flue design in locomotives limited steam generation because there was insufficient heating area between the hot tubes and the water in the boiler.

Initially, Booth and the L&M board allocated £100 for an experiment with a multi-tube boiler, but the result was deemed unsuccessful. The locomotive, named the “Lancashire Witch,” was eventually equipped with one main and two additional flues.

On 20 April 1829, the board of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway project passed a resolution to hold a competition to prove that their railway could be reliably operated by steam locomotives. Engineers at the time said that stationary engines were essential. The winner was promised a prize of £500, but only if the locomotive met certain strict requirements could it enter the trial.

As a result, the Rocket, with the first multi-tube boiler, was created in late 1829. There is a theory that Booth was the first to propose the boiler’s design, although Marc Séguin of France also claimed rights to the invention. But it seems that Booth came up with the idea independently of him, as the Rocket was in fact the first full-size locomotive to feature this important innovation. Moreover, the minutes of an L&M board meeting from 1827 contain a reference to a “smoke-consuming method of generating steam.”